Confusion on the Runway : Crash of USAir flight 5050

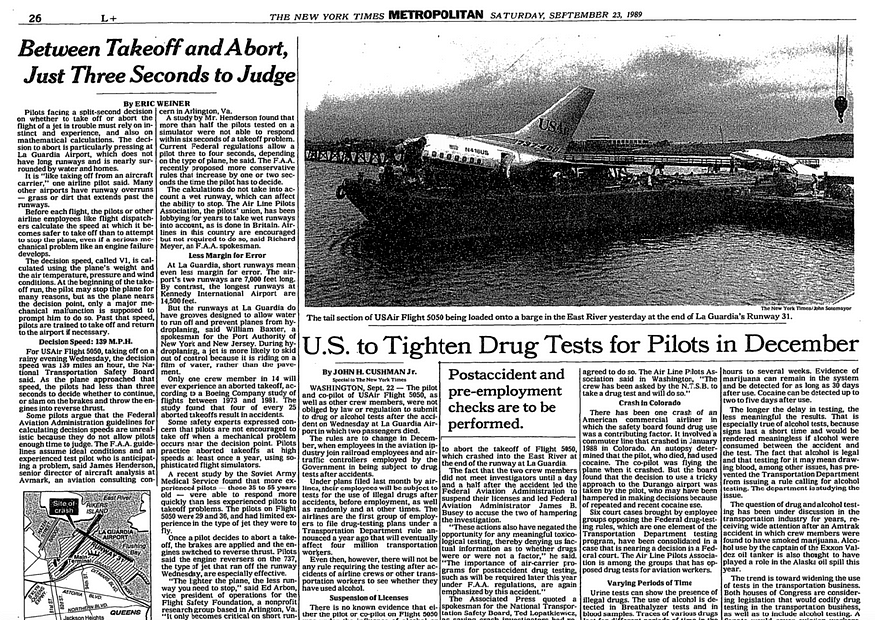

Rescuers approach the wreckage of USAir flight 5050 after it crashed into the East River following takeoff from LaGuardia. (New York Daily News)

On the 20th of September 1989, a USAir Boeing 737 began its takeoff roll on a stormy night at New York’s LaGuardia Airport. But as the plane sped down the runway, it began to pull to the left with increasing force. Fearing that they would crash, the captain decided to abort the takeoff — without checking whether or not it was already too late.

As the pilots tried desperately to stop it, USAir flight 5050 skidded off the end of runway 31 and plunged into Bowery Bay, where it struck a pier and broke into three pieces. By the time everyone was pulled from the water more than 90 minutes after the crash, two people were dead and another 21 injured.

Investigators would find that they didn’t need to die: the plane could have been stopped on the runway, and the initial pull to the left was caused not by the weather, but by the pilots themselves, who failed to check that the rudder was properly adjusted for takeoff. From there, errors compounded upon one another, building up in rapid sequence to send a perfectly sound airplane off the end of a runway that should have been long enough to allow it to stop.

In the latter half of 1989, legacy carrier USAir was in the final stages of acquiring Piedmont Airlines in what was then the largest airline merger in history. In order to smooth out what would surely be a complicated process, Piedmont airlines had agreed to begin training its pilots according to USAir procedures well in advance. By the time Piedmont hired 29-year-old rookie First Officer Constantine Kleissas in May of 1989, the merger was nearly complete, and he received the same training as anyone else at USAir. In fact, Piedmont Airlines no longer existed by the time he graduated, and when he arrived at Baltimore-Washington International Airport on September 20th for his first real unsupervised flight as a Boeing 737 pilot, the name on his plane read ‘USAir.’

Joining him on the crew roster that day was 36-year-old Captain Michael Martin, who held the rank of Major in the Air Force Reserves and still sometimes flew the Lockheed C-130 Hercules during his off days. After a brief stint as a flight engineer on the Boeing 727, Martin had gone through the same USAir-based 737 training program as Kleissas. Following just under three years as a first officer, he upgraded to captain exactly two months before the fateful flight. He had over 5,500 total hours, including 2,600 on the 737, but only 140 of them were as pilot in command. This was still much more than his extremely green first officer, who had yet to complete an unsupervised line flight and had accumulated just 22 hours in the real aircraft.

Martin and Kleissas flew from Baltimore to New York’s LaGuardia Airport that afternoon without incident. However, bad weather and traffic problems in the New York area had caused widespread delays and cancellations, with most flights out of the airport pushed back by several hours. Their next trip, USAir flight 1846 to Norfolk, Virginia, had already boarded when USAir informed them that the flight would be cancelled; the company instead wanted them to ferry the aircraft without passengers to Charlotte, North Carolina, where it was needed more urgently. After disembarking the frustrated passengers back at the gate, Captain Martin was informed of yet another change of plans: the trip to Charlotte would carry passengers who had been stranded after the cancellation of a previous flight. Martin expressed his displeasure at the change, which would cause the flight to take longer and push the crew close to the edge of their duty time limits.

Nevertheless, the unscheduled flight to Charlotte, designated flight 5050, went ahead. While the plane sat at the gate, Captain Martin went to ask the dispatcher a number of pointed questions, leaving First Officer Kleissas to supervise the boarding process. A number of people visited the cockpit during this time, including a Pan Am captain riding as a non-revenue passenger, who sat in the cockpit jump seat.

It is thought that when this captain sat down in the cockpit, he momentarily put his foot up to rest on the center pedestal, a fairly common habit among cockpit visitors. The pedestal is not a footrest, however, as it contains various controls, among which the foremost in this case was the rudder trim switch. Rudder trim is a system which allows the pilots to bias the rudder in a particular direction, making it possible to compensate for asymmetric drag or a consistent crosswind without having to constantly depress the rudder pedals.

But when cockpit jumpseaters rested their feet on the center pedestal, it was possible to bump the blade-style switch and swing it around to a left rudder trim position. Indeed, by the time USAir flight 5050 started its engines some while later, the switch was positioned to apply nearly maximum left rudder trim.

After Captain Martin returned to the plane, flight 5050 prepared to push back from the gate around ten minutes before 23:00. After the jet bridge was removed, a passenger service agent hailed Martin through the window and asked if they could put the jet bridge back and board additional passengers, but Martin refused, a decision that might have inadvertently saved lives.

With 57 passengers and 6 crew on board, flight 5050 left the gate at 22:52 and taxied to runway 31 for takeoff. While taxiing, the pilots ran through the before-takeoff checklist, which included checking the position of the trim. However, the checklist specifically said “stabilizer & trim,” an item which was sufficiently ambiguous that the pilots only checked the stabilizer trim, and not the rudder trim. Nor did Captain Martin notice what should have been a significant pull to the left during taxi, because the rudder trim also biases the nose wheel steering while on the ground.

Upon reaching the threshold of runway 31, First Officer Kleissas took control for the takeoff, as the pilots had previously agreed.

“You ready for it, guy?” Captain Martin joked.

“Here goes nothing,” Kleissas replied. He reached over to engage takeoff/go-around (TOGA) mode, but he accidentally pressed the autothrottle disconnect button instead. Consequently, when he properly pressed the TOGA switches a few seconds later, nothing happened, so he decided to advance the throttles to takeoff power manually.

“I got the steering till you, uh — okay, that’s the wrong button pushed,” said Martin.

“Oh yeah, I knew that, er — ” said Kleissas.

“It’s that one underneath there,” said Martin. “All right, I’ll set your power.” But despite his promise, he failed to fine-tune Kleissas’s rather imprecise power setting, in which neither engine was quite at full takeoff power and the left engine was about 3% slower than the right one.

As the plane accelerated down the runway, the rudder trim setting began to pull both the rudder and the nose wheel to the left, forcing Kleissas to hold his foot on the right rudder pedal to keep them going straight. However, Martin had said he would take care of the steering, and — unaware of his first officer’s rudder inputs — he simultaneously tried to hold the plane straight using the tiller, a small wheel next to the captain’s seat that controls the nose wheel steering.

But when a Boeing 737 approaches a speed of about 64 knots on a wet runway (and the runway that night was indeed wet), the aerodynamic force acting on the rudder becomes a more significant determinant of the plane’s direction than the nose wheel steering. Kleissas therefore needed to apply more right rudder to compensate for the increase in rudder authority at higher speed, but he didn’t, so the plane began to drift to the left. With Martin still holding the tiller straight as the plane veered left, the nose wheels started to skid, and at a speed of 62 knots one of them burst. Four seconds later, at a speed of 91 knots, a rumbling sound began to emanate from the wheels as the tires disintegrated.

At this point it would have been prudent to abort the takeoff. But instead, Captain Martin said, “got the steering,” an ambiguous phrase that only caused further confusion. Martin thought he said “you got the steering,” while First Officer Kleissas thought he heard “I’ve got the steering.” Consequently, both pilots stopped attempting to steer the plane straight. Flight 5050 immediately veered about seven degrees to the left, a course that would take them right off the side of the runway if they didn’t take immediate action.

What Martin failed to realize is that he had aborted after passing V1, the highest speed at which it is safe to abandon the takeoff. Before the flight he had calculated V1 to be 125 knots, but flight 5050 was moving at 130 knots when he announced they were stopping.

“USAir fifty fifty’s aborting,” First Officer Kleissas announced over the radio.

“Fifty fifty, roger, left turn at the end,” the controller replied.

But it suddenly became apparent that they were running out of runway. They should have had plenty of room to stop, but for some reason they didn’t! “Ah, we’re going off, we’re going off, we’re going off!” First Officer Kleissas shouted.

Still moving at a speed of 34 knots, USAir flight 5050 skidded off the end of the runway deck, dropped several meters, and slammed hard into the wooden pier that supported the approach lighting system extending into Bowery Bay. With a tremendous crunch, the pier collapsed and the plane broke into three pieces, coming to rest with its nose up in the air against what was left of the pier while the tail dropped down into the water.

The separation of the fuselage just aft of the wings caused rows 21 and 22 to swing upward and smash against the ceiling, crushing to death a Tennessee woman and her mother-in-law and trapping several others. The rest of the passengers and crew, discovering that they had survived the crash with relatively minimal injuries, immediately began to organize an evacuation. Flight attendants rushed to open the doors, but the L1 door wouldn’t open, and the L2 door had to be quickly shut after water started to pour in through the doorway. Those who evacuated through the overwing exits were able to stand on the partially submerged wings, with the help of the ditching lines, which some quick-thinking passengers had removed from their containers. However, those who jumped from the R1 and R2 passenger doors found themselves in the water without any good means of flotation — at the time, flights didn’t have to carry life jackets if they planned to stay within 50 nautical miles of shore. As they struggled in the water, several passengers became caught in a weak tidal current and drifted underneath the runway, which was constructed on pylons extending over the bay. Flight attendants threw life preservers and seat cushions to those who couldn’t swim, but many found that the seat cushions provided insufficient buoyancy to keep them afloat. Two of the flight attendants ended up jumping into the water to save drowning passengers.

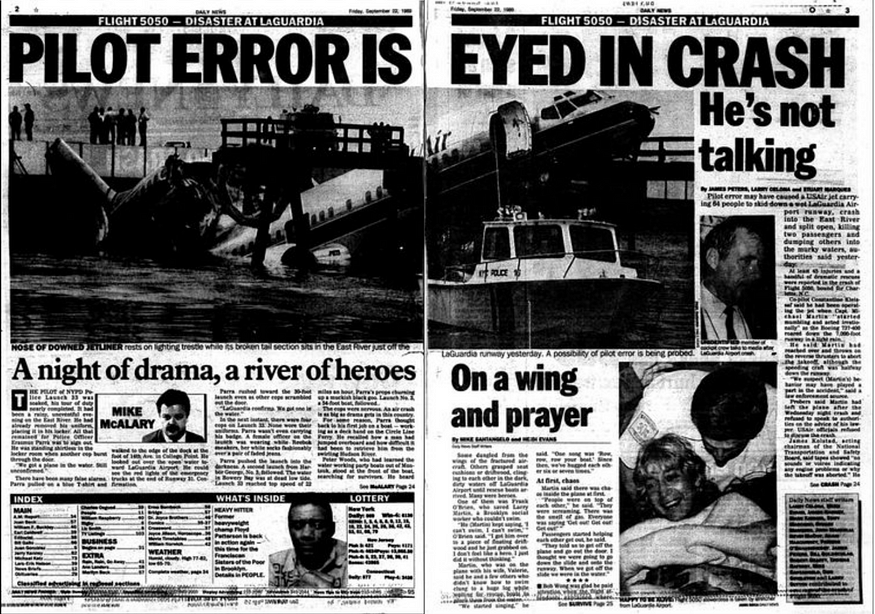

The rescue operation proved to be chaotic. The controller, upon noticing that the plane wasn’t going to stop in time, activated the crash alarm before the crash actually occurred, and fire trucks were on the scene within 90 seconds. Extracting the passengers from the water was another matter entirely, however. Those who were standing on the wings — including a single mother trying desperately to hold onto both a five-year-old and an 8-month-old infant — were rescued about 12 minutes after the crash. It took considerably longer to find all of those who had gone into the water, and the helicopters and boats that came to look for them had a hard time spotting the passengers amid the floating debris. Several passengers nearly drowned after being caught underneath the rotor wash of responding helicopters; others suffered serious injuries after swallowing jet fuel, and one woman sustained a fractured ankle and a lacerated hand after she was run over by a rescue boat. Firefighters also had to enter the precariously balanced fuselage to help the lead flight attendant and Captain Martin extract the passengers in seats 21F and 22A, who were pinned in the wreckage and could not be freed until 90 minutes after the crash. Following the successful rescue, Martin finally left the plane, the last person to do so.

Despite fears that many had drowned, by the time everyone was accounted for it became clear that the two passengers who died on impact were the only fatalities; everyone else had been rescued. Twenty-one people were injured, including Captain Martin, whose leg was pierced when shards of the wooden pier punched through the cockpit floor inside his footwell. But the crash could have been much worse: investigators would later note that if the plane were filled to capacity, more surely would have died.

When investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board arrived on the scene the morning after the accident, they expected to quickly interview the pilots to get a sense of what might have gone wrong. They also wanted to conduct routine tests to make sure the pilots weren’t under the influence of alcohol or drugs. But a request to ALPA (the pilots’ union) ten hours after the accident was rebuffed. ALPA first told the NTSB that they didn’t know where the pilots were, then eventually admitted that the union had moved them to an undisclosed location “so they could not be found by the media.” The NTSB wasn’t able to interview them until 44 hours after the accident, and even then ALPA only allowed it because the FAA threatened to subpoena them. By this time the pilots’ memories of the events were not as fresh and their urine samples would have been purged of any illegal substances.

Although rumors to the contrary persist, the NTSB was unable to find evidence which suggested that either pilot had been under the influence of alcohol at the time of the accident; in fact, a police officer trained in recognizing signs of alcoholism spoke to the captain just minutes after the crash and reported that he sounded perfectly sober.

It turned out that, like nearly all runway overrun accidents, a series of seemingly minor events added to the required distance until the plane simply ran out of room. The NTSB was eventually able to identify three main factors that prevented flight 5050 from stopping in time, without any one of which the crash would not have occurred.

A view of the plane from the edge of runway 31, looking in the direction of travel. (Author unknown)

The first factor was insufficient takeoff thrust. Neither engine ever quite reached the correct takeoff power setting, because the first officer accidentally disengaged the autothrottle. The autothrottle would have automatically set the correct takeoff thrust as soon as one of the pilots pressed the TOGA switches, but no one ever turned it back on, nor did Captain Martin correct First Officer Kleissas’s very rough throttle setting. This added 97 meters to the distance required to reach the speed at which Martin aborted the takeoff.

Second, Captain Martin aborted the takeoff after passing V1, a violation of proper procedures. Although V1 is defined as the speed after which the takeoff cannot be aborted without overrunning the runway, this is not always the case in practice; on flight 5050, the pilots derived V1 from a standard table of figures, while the runway was actually long enough to allow a successful rejected takeoff from a higher speed than the one they selected. Nevertheless, Captain Martin did not look at their speed before making his decision — if he had, he surely would have continued the takeoff, as the situation was not so critical as to warrant an emergency stop after passing V1. In fact, it was perfectly possible to steer the plane straight with the rudder pedals, get off the ground, and then fix the rudder trim while in the air (and in case their word was not enough by itself, the NTSB found several cases of pilots doing exactly this). In any case, aborting at 130 knots, instead of the V1 speed of 125 knots, added 151 meters to the stopping distance.

Police survey the crash site the day after the accident. (New York Daily News)

Finally, Captain Martin could have applied the brakes much faster than he did. Not believing stopping distance to be a major concern, he focused first on using differential braking to straighten their trajectory before applying maximum brake pressure. This delayed the onset of max braking by about three seconds relative to his usual reaction time, which added 240 meters to the stopping distance.

Martin also could have reduced this time even more if he had armed the autobrakes before takeoff. Both Boeing and USAir procedures recommended that pilots arm the autobrakes so that they can automatically apply maximum brake pressure as soon as a rejected takeoff is detected. However, some pilots declined to do this due to the airline equivalent of an old wives’ tale: they believed that the autobrakes would jerk the passengers uncomfortably during a low speed abort. (This was in fact false, because the autobrakes would only activate if the rejected takeoff occurred at high speed.) Investigators noted that this practice was dangerous because, while it was technically possible to make rudder inputs and apply maximum brake pressure at the same time, this required a pilot to place their feet in a very unnatural position; as a consequence, pilots could find themselves having to choose between braking and steering. Arming the autobrakes would eliminate this dilemma.

Because the crash occurred within sight of the Rikers Island prison complex, numerous correction officers participated in the response. It wasn’t the first time they had done so: the inset shows the aftermath of a 1957 plane crash on Rikers Island, in which both inmates and correction officers helped save the survivors. (New York Correction History Society)

In the case of USAir flight 5050, the Pan Am captain who visited the cockpit and sat in the jump seat denied having placed his feet on the pedestal; neither pilot touched the switch before or during the takeoff; and no evidence of a mechanical failure could be found. Investigators concluded that the Pan Am captain most likely put his feet up and then forgot, though they did not rule out the possibility that the switch moved when the first officer placed some papers on the center pedestal while the plane was at the gate. As a result of these findings, Boeing announced that it would change the rudder trim selector from a blade-type switch to a round knob which would not move when bumped, and that it would add a protective ridge around the knob to keep objects away from it.

No matter who accidentally moved the switch, the effects of the incorrect rudder trim position should have been evident during taxi. The rudder trim would have displaced the rudder pedals relative to each other by more than 11 centimeters, easily enough to notice, and Captain Martin would have needed to make constant inputs with the tiller to keep the plane moving straight as it made its way to the runway. And yet, in his initial interview, he didn’t mention noticing either of these things. Only much later did he tell investigators that he was vaguely aware of the displaced rudder pedals, but thought nothing of it because such a condition is common on the C-130, which he flew concurrently with the Boeing 737. Nevertheless, the NTSB felt that as a qualified 737 captain, he should have known that such a large rudder pedal displacement during taxi is abnormal.

The pilots also could have detected the discrepancy if they had followed the intent of the before takeoff checklist, which called on the pilots to check the position of the “stabilizer & trim.” However, if the pilots were not rigorously taught that this was supposed to include the rudder and aileron trim in addition to the stabilizer trim, it was understandable why they might have misinterpreted this line. In any case they checked only the stabilizer trim and not the others. (USAir later revised the wording to prevent confusion.)

During the takeoff itself, a breakdown in communication caused this relatively minor problem to escalate significantly. First Officer Kleissas did not tell Captain Martin that he was having difficulty holding the plane straight or that he was using the rudder to do so. Then, when a bang occurred at a speed of 62 knots, nobody suggested aborting the takeoff. Instead, Martin announced “Got the steering,” an ambiguous statement that did not make it clear who was supposed to be in control. This imprecise language led both pilots to relinquish control over the steering, and because First Officer Kleissas hadn’t mentioned that he was applying extra force with the rudder pedals or that he was about to remove this force, the sudden lurch to the left caught Martin totally by surprise. He tried to react using the tiller, even though the tiller is not effective at high speed, and he didn’t touch the rudder pedals at all, even though he could easily have used them to straighten the plane.

When the tiller failed to correct the drift to the left, he decided to abort the takeoff without checking their speed. As the pilot not flying, he should have been monitoring their speed in order to call out “80 knots” and “V1,” but because of the steering problem and the lack of clarity about who was flying the plane, nobody did this. As a result, he chose to reject the takeoff after the point where this was no longer allowed.

By this point it had become clear that the crash was preventable on every level. There were numerous opportunities for the pilots to notice the rudder trim setting and equally numerous opportunities for them to have used the controls available to them to straighten out and take off normally. None of these opportunities were taken. The pilots also could have prevented the crash by correcting the takeoff thrust setting, arming the autobrakes as recommended by the airline, or even by communicating more clearly about what they were experiencing as the plane sped down the runway. In the end, two people died, 21 people were injured, and a multi-million-dollar aircraft was destroyed because of complacency and inattention.

However, several of the critical decisions leading up to the accident could also be blamed on inexperience. The NTSB felt that it was unwise to pair a newly-promoted captain with a brand new first officer who only had 22 hours on the 737. Especially considering that this was First Officer Kleissas’s first unsupervised Boeing 737 takeoff, Captain Martin should have taken more steps to ensure he was ready (such as reviewing the rejected takeoff procedures), but his own inexperience might have prevented him from thinking of these contingencies.

After the 1987 crash of Continental Airlines flight 1713, another fatal accident caused by a series of banal errors before and during takeoff, the NTSB recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration require airlines to avoid pairing new captains with inexperienced first officers. However, the FAA had chosen to “promote” the policy rather than mandating it. Although such procedures are required today, they came too late to prevent the crash of USAir flight 5050.

The crash also might have been prevented if the pilots had received better training on how to communicate. Clear communication is a basic tenet of good crew resource management (CRM), a topic which was already being taught at several major US airlines. USAir, however, was not among them, and neither pilot had received any CRM training. (Although it is considered indispensable today, the FAA didn’t require airlines to provide this training until 1994.) If they had been trained on the principles of CRM, First Officer Kleissas might have mentioned that he was using the rudder to keep the plane straight, and Captain Martin might have made it clearer who would take control of the steering. This would have given the pilots the information they needed to stabilize the situation and successfully continue the takeoff.

In addition to the redesign of the rudder trim switch and the proposal to avoid pairing two inexperienced pilots, the NTSB also recommended that LaGuardia try to make the areas near the ends of its runways less hazardous to airplanes; that flight attendants receive hands-on water emergency drills; that airlines ensure pilots know how to extract maximum stopping performance during a rejected takeoff; and that pilots be required to arm the autobrakes (if available) whenever they take off on a runway that is wet or particularly short, among other suggestions. The NTSB also called on the Department of Transportation to create unified requirements for the provision of blood and urine samples from vehicle operators involved in accidents in all mass transit sectors. In its final report, the NTSB ripped into ALPA for holding the pilots so long after the crash, noting that this “complicated the investigation to a great degree.” Making no effort to hide their exasperation, the investigators then added, “The sequestering of the pilots for such an extended period of time in many respects borders on interference with a federal investigation and is inexcusable.” Indeed, if the pilots had tried to evade investigators for 44 hours after a crash without the protection of ALPA, they probably would have been arrested.

Unfortunately, despite the promised improvements, the events of the years following the crash of flight 5050 have largely consigned the accident to a footnote in the margins of greater tragedies. In 1991, 35 people died when a USAir flight collided with a Skywest Metroliner at LAX due to an error by the air traffic controller. In 1992, USAir flight 405 crashed off the same runway at LaGuardia, killing 27 of the 51 people on board, due to an accumulation of ice on the wings. Then in July 1994, USAir flight 1016 crashed near Charlotte after the pilots became disoriented in wind shear, killing 37; and two months later USAir flight 427 crashed in Pittsburgh, killing 132, due to a malfunction of the rudder. Although some of these accidents couldn’t conceivably be pinned on USAir, by the end of 1994 the airline had managed to accrue the worst safety record of any major US carrier. Today, however, USAir no longer exists, and most of the factors which led to the crash have been rectified. The last of the safety improvements sought by the NTSB after flight 5050 came only in 2015, when LaGuardia installed specialized Engineered Materials Arrestor Systems on all its runways, ensuring that no airliner will ever again run off the end and fall into the East River.