Great Depression & The Federal Researve : An Analysis of United States Federal Government Monetary Policy from 1929 to 1934

Great Depression & The Federal Researve : An Analysis of United States Federal Government Monetary Policy from 1929 to 1934

“[The crash] came with a speed and ferocity that left men dazed. The bottom simply fell out of the market… Where was it going to end?” proclaimed New York Times reporter Elliot V. Bell.2 On Thursday, October 24th, 1929, stock prices collapsed and caused investors to lose 100 billion in present-day dollars. Speculators shouted across the New York Stock Exchange, desperately trying to sell their shares to anyone who would buy.3 Because the crash caused them to lose confidence in their investments, they decided to sell their stocks, further lowering stock prices and causing other investors to sell. October 24th became known as “Black Thursday” because of the magnitude and eventual consequences of the market crash. In response, leaders in the banking industry met at the residence of John Pierpont Morgan, founder of the J.P. Morgan investment bank. These leaders announced that they would buy stocks at high values to stop the fall, contributing millions of dollars to their effort. Though temporarily reducing other investors’ level of panic, the investors’ plan failed. The stock market fell dramatically once again on the next Tuesday, October 29th, also known as “Black Tuesday.” Some stocks even lost 90 percent of their value in one day.4

Although the stock market crash was dramatic, it did not cause the Depression alone. Only 2.5 percent of Americans had brokerage accounts, yet the vast majority of Americans suffered as a result of the Great Depression.5

At the heart of the Depression was a failure to properly manage monetary policy. The Herbert Hoover administration’s lack of experience with monetary policy and Hoover’s reliance on community strength without government interference led him to withhold federal aid during the Great Depression. “Where was it going to end?” asked the New York Times. By 1933, the unemployment rate grew from a low of 3.2 percent to a high of 24.9 percent and remained above 20 percent until 1935. National income in present-day dollars fell 35.7 percent, from 1.109 trillion dollars in 1929 to 0.817 trillion dollars in 1933.6 The Depression detrimentally affected the physical health of the country; for example, millions of Americans suffered from malnutrition because they could not afford food. In addition, the Depression caused mental health problems, contributing to an estimated 5,800 additional suicides per year between 1928 and 1932, an 22.8 percent increase.7 Unlike Hoover, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt successfully alleviated the Depression because he trusted in federal response to crises and learned from Hoover’s mistakes. Whereas the Hoover administration’s tight monetary policy and lack of government spending heavily contributed to the severity of the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal policies of government spending and loose monetary policy mollified the effects of the Depression.

Several decades before Black Thursday and prior to the 1913 establishment of the Federal Reserve, state governments regulated trusts. Trusts were financial institutions that accepted deposits and gave short-term loans to banks to ensure that the banks had sufficient available funds. Because withdrawals from trusts were infrequent, they only held about five percent cash reserves, in contrast to the roughly twenty-five percent cash reserves held by nationally regulated banks. This discrepancy was highlighted by the Panic of 1907, a financial crisis. When some speculators lost money on an investment in the United Copper Company in 1907, they attempted to withdraw millions of dollars from trusts. The trusts could not return these funds and went bankrupt. Several banks also went bankrupt because trusts could no longer lend them money.8 After stocks lost millions of dollars in value and several financial institutions failed, the American public and politicians supported greater federal regulation of the banking industry. As a result, Congress established the Federal Reserve on December 23rd, 1913. Congress created the Federal Reserve to centrally regulate all American financial institutions and support them in times of crisis.9

In its infancy, the Federal Reserve managed the United States economy using the gold standard, a monetary system that defines the value of a country’s currency in terms of gold. Under the gold standard, every dollar was backed by gold in order to reduce the likelihood of inflation and keep international exchange rates roughly constant.10

In the 1910s, the price of gold was 20.67 dollars per ounce, meaning that the Federal Reserve was obligated to offer an ounce of gold in exchange for 20.67 dollars.11

The 1920s ushered in an era of rapid expansion in consumer spending and the availability of quality goods. For example, automobile sales per year rose from 1.5 million in 1921 to 4.5 million in 1929.12 During this period, the Federal Reserve mostly regulated the economy by raising and lowering interest rates. Because interest rates determine the price of credit, this reduction incentivized Americans to take out loans to buy goods or property, whereas higher rates did the opposite. The Federal Reserve wanted to keep interest rates low to stimulate spending; however, it did not want to dramatically lower rates in fear of causing excessive economic growth and an inflationary crisis.13 Consumer spending increased the inflation-adjusted total private debt and Gross Domestic Product by 51.4 percent and 40.7 percent, respectively.14 Although credit-fueled expansion temporarily succeeded in the 1920s during a period of economic growth, excessive debt caused problems when the economy declined after Black Thursday. The saturation of the market was also detrimental. After going into debt to buy cars, radios, and other products in the 1920s, Americans no longer needed to buy more of these products. When inventories rose, executives reduced production and fired workers, reducing consumer demand and damaging the economy. Debt and market saturation caused a vicious cycle. Americans bought fewer products, leading to more unemployment, in turn causing Americans to buy fewer products because they did not have a source of income.15 Unfortunately, the federal government and Federal Reserve during Herbert Hoover’s presidency failed to mollify this problem.

Herbert Hoover served as president of the United States between March 4th of 1929 and 1933. Hoover believed that high tariffs would increase domestic purchases of American products as well as protect American farmers and manufacturers from competitors abroad. As global markets receded, Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, the highest tariff in American history. Other countries reciprocated, leading to a trade war that reduced international yearly trade from 36 billion dollars in 1929 to 12 billion dollars in 1932. American exports dropped by 78 percent during this time period.16 Hoover’s beliefs stopped his administration from providing federal relief from the Great Depression. He believed in associationalism, the assumption that Americans would voluntarily maintain a network of organizations to help those in need. Hoover thought that businesses would promote employee-friendly practices, such as high wages and good working conditions, to benefit the economic good of the country. Arguing it would discourage Americans from looking for work, Hoover also opposed government aid. In his view, associationalism would encourage individual action to grow the American economy. Hoover was adamant in his beliefs during the Great Depression, responding to America’s pleas for help by promoting volunteerism. He asked company executives not to withdraw investments or fire employees and urged state and local charities to help people in need. The Hoover administration’s most concrete humanitarian policy was the establishment of the President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief (POUR) to direct the charitable work of private organizations. Unfortunately, these organizations did not have the funds to fulfill the needs of the millions of Americans left without a job or home. In New York, twenty-five percent of private charities closed by 1932 due to insufficient funds, whereas in Atlanta, some charities operated with only 1.30 dollars in available funding per family in need.17

The Hoover administration’s tight monetary policy also caused problems during the Depression. After the stock market crash of 1929, the Federal Reserve panicked, raised interest rates, and tightened credit, leading banks to offer fewer loans and pressure debtors to pay their balance. Instead, the Federal Reserve should have lowered interest rates to increase the number of loans that banks offered, thereby increasing the amount of spending.18 Bank customers worried that the reduction in bank loans signaled problems in the financial market and attempted to collect their money from the banks en masse before they failed.

Because banks only keep a fraction of deposits available for customers to withdraw, banks were unable to pay all of the customers who wanted their deposits in cash. Failures of some banks increased panic and led to more customers attempting to collect their deposits, causing even more bank failures.19 This phenomenon, known as a “bank run,” began in 1930 in Nashville, Tennessee and quickly spread throughout the Southeast.20 These failures were widespread and devastating. 1,352 banks failed in 1930 and the number of failures rose to 2,300 in 1932. This caused widespread disruption in credit markets and resulted in Americans losing millions of dollars in savings and deposits.21

Farmers also suffered from tight monetary policy. Demand for farm goods stayed constant throughout the 1920s while production increased, resulting in a price decrease. Farmers could not pay back their loans, and when the Federal Reserve increased interest rates, it made it even more difficult for them to pay back the banks.22 Although Hoover could not directly control interest rates, he could have pressured Federal Reserve chair Eugene Meyer to lower interest rates or appointed a Federal Reserve chair who supported looser monetary policy. However, Meyer is not largely responsible for worsening the Depression, as the Federal Reserve was only founded in 1913, and both Federal Reserve and federal government officials were still trying to understand the role of monetary policy.23

In 1932, Hoover finally attempted to stimulate America’s industry and economy by giving loans to several private corporations through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). However, Hoover’s efforts fell short because the RFC only extended credit to corporations, rather than individuals in need. The limitations of the RFC led New York Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia and many others to call it a “millionaire’s dole.” 24

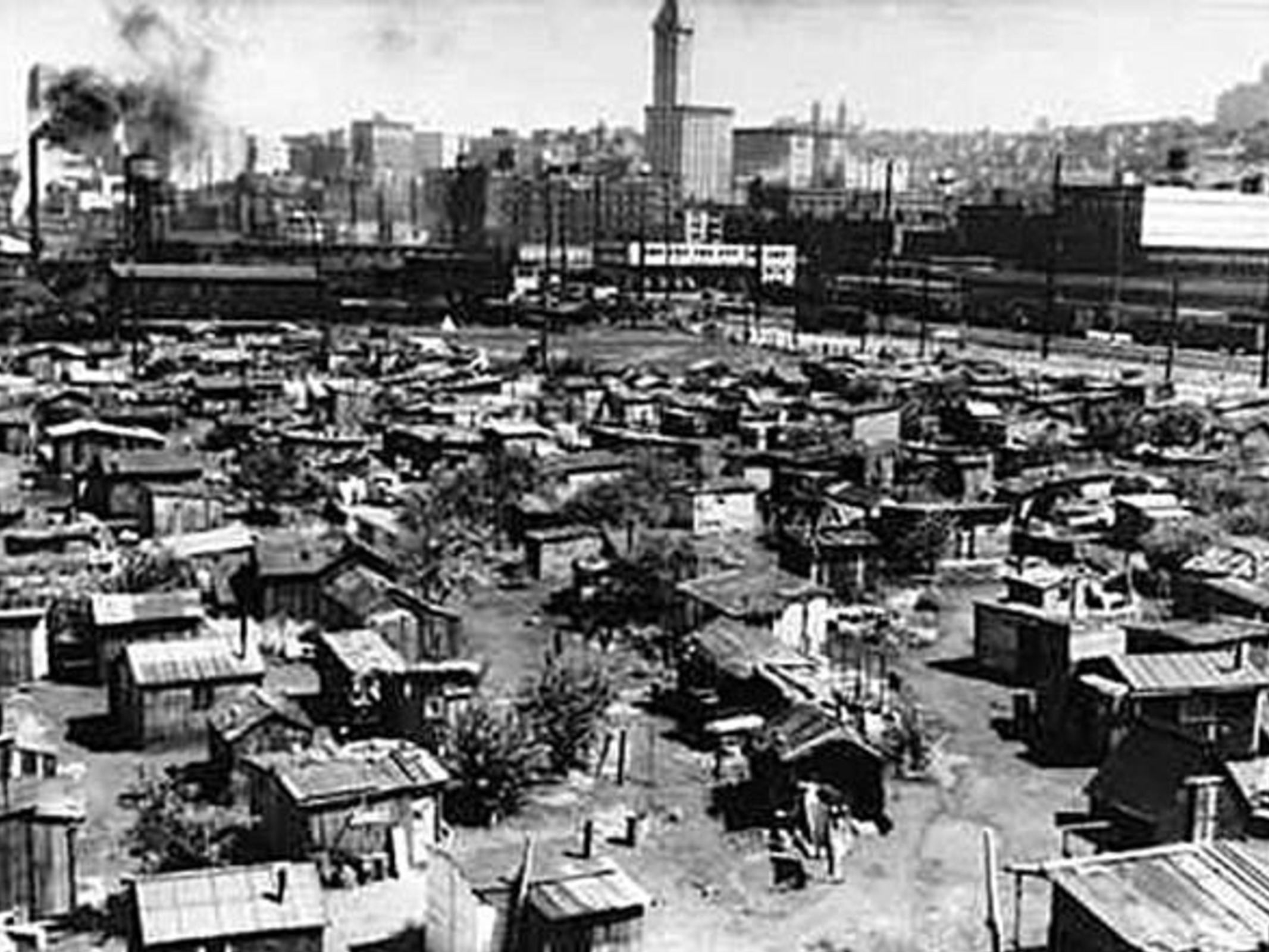

Hoover’s failure to provide humanitarian aid to Americans in need or to expand the money supply continued until the end of his presidency. In the summer of 1932, Congress debated the Wright Patman Bonus Bill. The bill proposed giving bonuses to World War I veterans immediately rather than distributing them in 1945. If passed into law, the bill would have given much needed cash to World War I veterans and benefited the economy because the veterans would have spent the money. During the deliberation of the bill, more than fifteen thousand unemployed veterans and their families, called the “Bonus Army,” created a city of tents in Anacostia Flats, across the Potomac River from Washington DC. This tent city, which came to be known as “Hooverville,” resembled camps of homeless and unemployed people in other cities. Hoover opposed the bill, and it ultimately was not passed by the Senate. After the bill failed, the Bonus Army pressured Congress to reconsider. Hoover responded by calling them “insurrectionists” and ordering them to leave. When many refused, Hoover ordered General Douglas MacArthur to storm the tent city and round up the bonus army with police, army troops, and military equipment. The media took pictures of troops chasing down veterans, spraying children with tear gas, and torching the tent city.25 Hoover’s instigation of a public outrage instead of assisting those in need typified the ethos of his administration’s policy during the beginning of the Great Depression.

After winning the Democratic nomination for the 1932 presidential election, Roosevelt stated in a speech, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.”26 Throughout the campaign, the media called Roosevelt’s plans to alleviate the Great Depression “the New Deal.” Voters liked Roosevelt’s ideas and in the general election, he defeated incumbent Republican Herbert Hoover in a landslide, winning fifty-seven percent of the popular vote and 472 out of 531 electoral votes. During his time in office, Roosevelt gave his presidential addresses in the form of fireside chats.27 During the addresses, Roosevelt explained complicated concepts in layman’s terms and spoke informally and personally to assuage the worries of the American people. Roosevelt gave the first and second fireside chats on March 12th and May 7th, 1933. Because they contained information on Roosevelt’s policies, historians and economists used them to understand Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression. Analysis of the fireside chats, as well as other primary sources from the Depression, established two main interpretations of federal economic policy during the Great Depression: Keynesian economics and monetarism.

Advocates of Keynesian economics, created after the Great Depression and named after British economist John Maynard Keynes, argue that higher government spending and lower taxes were necessary to end the Great Depression.28 Although Congress under Roosevelt did not lower taxes, some of Roosevelt’s policies represented Keynesian ideas. The federal government spent 41.7 billion dollars on the New Deal, roughly forty percent of America’s gross domestic product at the time.29

In the second fireside chat, Roosevelt cited the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a federal program to provide two hundred and fifty thousand jobs in forestry and flood prevention.30 Furthermore, Roosevelt underscored the Emergency Railroad Transportation Act, which used federal funds to aid railroad companies in need and granted them legal exceptions.31 Roosevelt’s non-banking response to the Great Depression centered around two main efforts to stabilize and organize the American economy: the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The AAA attempted to raise the price of food so that farmers could pay off their loans, and the NRA suspended antitrust laws to allow businesses to collaborate amongst themselves.32 Under Roosevelt, Congress also established organizations such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Whereas the FERA gave cash directly to failing state-run relief organizations, the TVA built hydroelectric dams in the economically underdeveloped Tennessee River area.33 Finally, the Civil Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration hired individuals to work on infrastructure projects organized by local governments.34

Advocates of monetarism argue that changes in the money supply, such as increasing or decreasing the amount of dollars in circulation, have the biggest impact on economic growth.35 Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression also contained monetarist policies. For example, Roosevelt closed American banks for four days while Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act. The Act sought to increase public confidence in banks by creating new regulations that banks needed to meet in order to reopen.36In the first fireside chat, Roosevelt explained new banking regulations. He also asked the public to deposit money in banks and trust their reliability. If the public had continued to withdraw from banks at the same rates, additional banks would have gone bankrupt and even more people would have lost their savings. After Roosevelt’s national address, deposits heavily outnumbered withdrawals across the country. In June of 1933, Roosevelt’s Congress successfully passed the Glass-Steagall Banking Act. The Act attempted to stabilize the financial market by preventing commercial banks, which accept deposits from the general public, from trading certain stocks and bonds. The Act also charged banks premiums in order to insure commercial deposits up to 2,500 dollars through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). This measure reduced the frequency of bank runs because people no longer worried about losing their savings in the event of a bank failure.37 Only 373 banks failed between 1934 and 1941, a drastic improvement from the several thousands of yearly failures of the early 1930s.38

In turn, a reduction in bank failures allowed Americans to spend more and stimulate the economy due to an expansion of loan availability.39

Roosevelt’s second fireside chat took place three weeks after he suspended the gold standard on April 20th, 1933.40 During the national address, Roosevelt stated that the lack of available bank credit and the widespread mortgage foreclosures damaged the American economy. Roosevelt also emphasized that the gold standard contributed to this problem by restricting the money supply.41

The United States possessed a limited supply of gold during the Great Depression, creating a double-bind. Raising interest rates would ensure that international investors kept their investments in the United States, but would stop Americans from spending enough money to stimulate the economy. Lowering the rates would encourage Americans to spend, but would cause investors to convert their money to gold and invest it somewhere else, decimating America’s gold reserves and jeopardizing the stability of the American economy.42 When he suspended the gold standard, Roosevelt ordered Americans to exchange gold for dollars in order to increase the money supply and gold reserves at Fort Knox. On January 30th, 1934, the Gold Reserve Act prohibited the private ownership of gold, with exceptions for licensed individuals. Roosevelt also increased the price of gold from 20.67 dollars per ounce to 35 dollars per ounce, further expanding the money supply.43 Partially as a result of the Roosevelt administration’s policies, the inflation-adjusted United States GDP grew by 43.2 percent.44 During the same period, the unemployment rate in the United States dropped from 24.9 percent to 14.3 percent.45

The response to the New Deal was not entirely positive. Because Roosevelt passed New Deal legislation through Congress in a disproportionately short period of time, he seemed to lead both the executive and the legislative branches of the federal government. Roosevelt’s enormous power raised questions about the constitutionality of his actions. However, politicians seldom focused on the procedural legality of Roosevelt’s actions because Americans needed quick relief from the Great Depression.46 After the worst of the Depression passed, politicians and lawyers began to investigate the constitutionality of the New Deal. The Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional in 1935 and the AAA unconstitutional in 1936.47 Roosevelt also faced opposition from Louisiana democratic Senator Huey Long, California public health official Francis Townsend, and priest and talk show host Reverend Charles Coughlin. All three argued that Roosevelt’s programs did not provide enough aid to poor and unemployed Americans. For example, Huey Long’s Share Our Wealth program proposed that the federal government redistribute the assets of wealthy Americans to poorer Americans through a guaranteed minimum income. Americans throughout the country created more than 27,000 Share Our Wealth clubs, and Long traveled the country to explain his ideas to many poor and unemployed Americans.48

Roosevelt faced opposition from conservative politicians and business leaders as well. Business Republicans disliked Roosevelt’s regulation of industry and use of funding for public works and employment programs. Southern Democrats who originally supported Roosevelt disliked programs that challenged the Southern status quo, where landowners held almost complete control over tenants. These conservative interests opposed New Deal policies that provided aid to tenant farmers and gave them collective bargaining and unionization power.49 Despite the opposition, Roosevelt was a very popular president. In the 1936, 1940, and 1944 presidential elections, Roosevelt’s closest result in the electoral college was 432 to 99 votes.

Roosevelt also won between fifty-three and sixty percent of the popular vote in each election.50 Though historians lack data for presidential approval ratings before 1941, between 1941 and 1943 FDR’s approval ratings ranged between sixty-five and eighty-three percent.51

The Great Depression has heavily informed the federal government’s present understanding of monetary policy. Both President Hoover and President Roosevelt attempted to implement successful monetary policy, yet Roosevelt was more successful. Hoover and Roosevelt created precedents of successful and unsuccessful actions in times of crisis, setting the foundations of modern understanding of monetary policy. Ben Bernanke, Federal Reserve Chair during the 2008 financial crisis, studied the Great Depression as a student and during his career, particularly focusing on the pillars of monetary policy that Hoover and Roosevelt erected. Bernanke greatly learned from his studies: In the 2008 financial crisis, he lowered interest rates, recommended large amounts of federal spending, and pushed for the federal bailouts of some banks.52 Federal spending succeeded in 2008 as well: unemployment dropped from 9.9 percent in 2009 to 5.6 percent in 2014.53 The cost was also similar: the increase in federal debt as a fraction of GDP was 30.3 percent during the New Deal and 32 percent during the response to the 2008 financial crisis.54

The federal response to the Great Depression also informed some of Congress’ future actions. The FDIC deposit insurance that Roosevelt created with the Glass-Steagall Banking Act of 1933 still exists, and Congress has gradually raised its coverage from 2,500 to 250,000 dollars.55 However, Congress did not always heed the lessons of the Great Depression . Sections 16, 20, 21, and 32 of the original Glass-Steagall Act prevented commercial banks from trading many stocks and bonds. Members of Congress included this provision in the Act because they believed that the risk-prone behavior of bankers caused the Great Depression.56 Given the many factors that contributed to the Great Depression, such views exaggerate the role of risky investing; however, the risky behavior of investors heavily contributed to the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Nonetheless, many believed that involving the savings and lives of average Americans in investment banking made the country vulnerable to another crisis.57

In 1999, Congress repealed these sections of the Glass-Steagall Act through the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.58 The years before the 2008 financial crisis proved the writers of the original Glass-Steagall Act right. Reckless investors ignored the advice of colleagues who warned them of their investments’ excessive risk. Ultimately, these careless mistakes caused millions of Americans to lose their homes, their jobs, and their savings.59 Fortunately, there was no Herbert Hoover to worsen the crisis this time around. Rather, his response contributed to the understanding of how to allay the crisis.

Great Depression & The Federal Researve : An Analysis of United States Federal Government Monetary Policy from 1929 to 1934 Written by Lorenzo Lizzeri

Great Depression & The Federal Researve : An Analysis of United States Federal Government Monetary Policy from 1929 to 1934 Bibliography

1 Adam Chandler. “How the Great Depression Still Shapes the Way Americans Eat.” The Atlantic, December 22, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/12/great-depression-eat/511355/.

2 Elliot Bell. “Panic and Crash: 1929.” New York Times, 1938.

3 George Donelson Moss, The Rise of Modern America: A History of the American People, 1890–1945 (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1995), 185–186.

4Ibid., 185-186

5 George Donelson Moss, The Rise of Modern America: A History of the American People, 1890–1945 (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1995), 185–186.

6 Bureau of Economic Analysis. “National Income and Product Accounts Tables: Table 1.1.3. Real Gross Domestic Product.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=survey; Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Unemployment Rate, 1929-2020.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

7 Luo, Feijun, Curtis S. Florence, Myriam Quispe-Agnoli, Lijing Ouyang, and Alexander E. Crosby. “Impact of Business Cycles on US Suicide Rates, 1928–2007.” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. 6 (June 2011): 1139–46. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300010; Janet Poppendieck. Breadlines Knee-Deep in Wheat: Food Assistance in the Great Depression, 1-15. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

8 Kellogg Insight. “Why the Panic of 1907 Led to a Recession.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/why-the-panic-of-1907-led-to-a-recession. 9 “The Panic of 1907 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

10 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 135-154.

11 “Gold Reserve Act of 1934 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

12 Lorna C. Mason. America’s Past and Promise. Evanston, Illinois: McDougal Littell, 1998, 654-675. 3

13 Board of Governors of the United States Federal Reserve System (U.S.), Mark Carlson, and Burcu Duygan-Bump. “The Tools and Transmission of Federal Reserve Monetary Policy in the 1920s.” FEDS Notes 2016, no. 1871 (November 2016). https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.1871.

14 Elwyn Bonnell. “Public and Private Debt in the United States.” United States Federal Reserve, September 1946. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/SCB/pages/1945-1949/46397_1945-1949.pdf; United States Census Bureau. “Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1957.” United States Federal Reserve, 1957, 131. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/histstatus/hstat_1957_cen_1957.pdf. 15 George Donelson Moss, The Rise of Modern America: A History of the American People, 1890–1945 (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1995), 185–186.

16Ibid., 185-186.

17 David M. Kennedy and C. Vann Woodward. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929 – 1945. The Oxford History of the United States, C. Vann Woodward, general ed.; Vol. 9. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, 70-103.

18 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters, Chapter V. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 80-104.

19 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters, First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 105-134.

20Corporate Finance Institute. “Bank Run – Liquidity & Causes of Bank Runs.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/other/bank-run/.

21David M. Kennedy and C. Vann Woodward. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929 – 1945. The Oxford History of the United States, C. Vann Woodward, general ed.; Vol. 9. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, 65-68.

22Robert S. McElvaine, The Great Depression: America, 1921–1940 (New York: Random House, 1984), 36. 23 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 80-104.

24 David M. Kennedy and C. Vann Woodward. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929 – 1945. The Oxford History of the United States, C. Vann Woodward, general ed.; Vol. 9. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, 76.

25 Ibid,, 92.

26 “Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States : from George Washington 1789 to George Bush 1989.” Text. Yale University. Accessed May 27, 2021. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/froos1.asp. 27 Winfield, Betty Houchin. FDR and the News Media. Columbia University Press Morningside ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, 146.

28 “What Is Keynesian Economics?” International Monetary Fund. Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/09/basics.htm.

29 Price Fishback, and Valentina Kachanovskaya. “The Multiplier for Federal Spending in the States During the Great Depression.” The Journal of Economic History 75, no. 1 (March 2015).

30 Neil Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 43-77.

31 “Second Fireside Chat | The American Presidency Project.” Accessed May 2, 2021.

32 Ellis W. Hawley, The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969), 19-34; Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1986), 217.

33 Neil Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, 3-16); David M. Kennedy and C. Vann Woodward. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929 – 1945. The Oxford History of the United States, C. Vann Woodward, general ed.; Vol. 9. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, 131-159. 34 Bonnie Fox Schwartz, The Civil Works Administration, 1933–1934: The Business of Emergency Employment in the New Deal (Princeton, NJ1: Princeton University Press, 1984), 72-101, 239-259.

35 “What Is Monetarism?” International Monetary Fund. Accessed May 27, 2021.

36 “Emergency Banking Act of 1933 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/emergency-banking-act-of-1933.

37 “Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/glass-steagall-act.

38 “FDIC: Managing the Crisis: Chronological Overview – Chapter Two: 1933-1979.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/4webcsey.

39 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 105-134.

40“Roosevelt’s Gold Program | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

41 “Second Fireside Chat | The American Presidency Project.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

42 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 105-134.

43 “Gold Reserve Act of 1934 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

44 Bureau of Economic Analysis. “National Income and Product Accounts Tables: Table 1.1.3. Real Gross Domestic Product.

https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=survey. Accessed May 27, 2021.

45 Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Unemployment Rate, 1929-2020.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?bls.

46 William E. Leuchtenberg. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal: 1932-1940. New York: Harper and Row, 1963, 41-62.

47 William E. Leuchtenburg, The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 213-236.

48 Colin Gordon, New Deals: Business, Labor, and Politics in America, 1920–1935 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 204-239.

49 Colin Gordon. New Deals: Business, Labor, and Politics in America, 1920–1935. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 280-306.

50 “Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://uselectionatlas.org/. 51 “Presidential Job Approval | The American Presidency Project.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/presidential-job-approval.

52 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters, 60-79. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

53 Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Unemployment Rate, 1929-2020.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?bls

54 “Which Was Bigger: The 2009 Recovery Act or FDR’s New Deal.” St. Louis Federal Reserve. Accessed May 27, 2021.

55 Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters. First Edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016, 60-79.

56 “Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/glass-steagall-act.

57 NPR.org. “Death Of The Brokerage: The Future Of Wall Street.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=94894707.

58 Federal Trade Commission. “Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/privacy-and-security/gramm-leach-blile-act. 59 Sorkin, Andrew Ross. Too Big to Fail: The inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System from Crisis–and Themselves. New York: Viking, 2009, 1-30.

Adam Chandler. “How the Great Depression Still Shapes the Way Americans Eat.” The Atlantic, December 22, 2016.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/12/great-depression-eat/511355/. Andrew Ross Sorkin. Too Big to Fail: The Inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System from Crisis–and Themselves. New York: Viking, 2009.

Corporate Finance Institute. “Bank Run.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/other/bank-run/. “Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/glass-steagall-act.

Barry J. Eichengreen. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919-1939. NBER Series on Long-Term Factors in Economic Development. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Board of Governors of the United States Federal Reserve System (U.S.), Mark Carlson, and Burcu Duygan-Bump. “The Tools and Transmission of Federal Reserve Monetary Policy in the 1920s.” FEDS Notes 2016, no. 1871 (November 2016).

Bonnie Fox Schwartz. The Civil Works Administration, 1933–1934: The Business of Emergency Employment in the New Deal. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “National Income and Product Accounts Tables.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1 21=Survey.

Caroline Bird. The Invisible Scar. New York: McKay, 1966.

Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science. Fully rev. and Updated. New York: W. W. Norton, 2010.

Charles J. Wheelan. Naked Money: A Revealing Look at What It Is and Why It Matters. First edition. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Colin Gordon. New Deals: Business, Labor, and Politics in America, 1920–1935. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

“Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://uselectionatlas.org/.

David M. Kennedy and C. Vann Woodward. Freedom from Fear: The American People in 15

Depression and War, 1929 – 1945. The Oxford History of the United States, C. Vann Woodward, general ed.; Vol. 9. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001. NPR.org. “Death Of The Brokerage: The Future Of Wall Street.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=94894707.

Elliot Bell. “Panic and Crash: 1929.” New York Times, 1938.

https://www.originalsources.com/Document.aspx?DocID=US3JCSGUWU4ZP3X. Ellis Wayne Hawley. The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence. New York: Fordham University Press, 1995.

Elwyn Bonnell. “Public and Private Debt in the United States.” United States Federal Reserve, September 1946.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/SCB/pages/1945-1949/46397_1945-1 49.pdf.

“Emergency Banking Act of 1933 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/emergency-banking-act-of-1933. Eric Rauchway. The Money Makers: How Roosevelt and Keynes Ended the Depression, Defeated Fascism, and Secured a Prosperous Peace. New York: Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Book Group, 2015.

“FDIC: Managing the Crisis: Chronological Overview – Chapter Two: 1933-1979.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/chronological/1933-79.html#:~:text=In20 the%20eight%2Dyear%20period,of%20them%20were%20small%20banks. Federal Trade Commission. Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, May 27, 2021.

https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/privacy-and-security/gramm-leach-blile -act.

Feijun Luo, Curtis S. Florence, Myriam Quispe-Agnoli, Lijing Ouyang, and Alexander E. Crosby. “Impact of Business Cycles on US Suicide Rates, 1928–2007.” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. 6 (June 2011): 1139–46.

Gavin Wright. Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War. New York: Basic Books, 1986.

George Donelson Moss. The Rise of Modern America: A History of the American People, 1890–1945. New York: Prentice Hall, 1995.

“Gold Reserve Act of 1934 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/gold-reserve-act.

“How the Fed Has Responded to the COVID-19 Pandemic | St. Louis Fed.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2020/august/fed-response-covid19-pandemic. “Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States : from George Washington 1789 to George Bush 1989.” Text. Yale University. Accessed May 27, 2021. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/froos1.asp.

Janet Poppendieck. Breadlines Knee-Deep in Wheat: Food Assistance in the Great Depression. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Jason Scott Smith. Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Kenneth Finegold and Theda Skocpol. State and Party in America’s New Deal. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

Kristi Andersen. The Creation of a Democratic Majority, 1928–1936. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Lee E. Ohanian and Harold L. Cole. “The Great Depression in the United States From A Neoclassical Perspective.” Quarterly Review 23, no. 1 (December 1999). https://doi.org/10.21034/qr.2311.

Lizabeth Cohen. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. 2nd ed., new Ed. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Lorna C. Mason. America’s Past and Promise. Evanston, Illinois: McDougal Littell, 1998. Michael A. Bernstein. The Great Depression: Delayed Recovery and Economic Change in America, 1929-1939. Studies in Economic History and Policy: USA in the Twentieth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Michael Lewis. The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2010.

Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960: Princeton University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400829330. Neil Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Paul Krugman. “Opinion | Misguided Monetary Mentalities.” The New York Times, October 12, 2009, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/12/opinion/12krugman.html. “Presidential Job Approval | The American Presidency Project.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/presidential-job-approval. Price Fishback, and Valentina Kachanovskaya. “The Multiplier for Federal Spending in the

States During the Great Depression.” The Journal of Economic History 75, no. 1 (March 2015): 125–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050715000054.

Robert S. McElvaine. The Great Depression: America, 1921–1940. New York: Random House, 1984.

“Roosevelt’s Gold Program | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/roosevelts-gold-program.

“Second Fireside Chat | The American Presidency Project.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/second-fireside-chat.

“The Panic of 1907 | Federal Reserve History.” Accessed May 27, 2021.

Thomas K. McCraw. TVA and the Power Fight, 1933–1939. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1971. “Unemployment Rate, 1929-2020.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021. Lehman Brothers

United States Census Bureau. “Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1957.” United States Federal Reserve, 1957.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/histstatus/hstat_1957_cen_1957.pdf. “What Is Keynesian Economics?” International Monetary Fund. Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/09/basics.htm.

“What Is Monetarism?” International Monetary Fund. Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/03/basics.htm.

“Which Was Bigger: The 2009 Recovery Act or FDR’s New Deal.” St. Louis Federal Reserve. Accessed May 27, 2021.

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2017/may/which-bigger-2009-recovery-act-. Kellogg Insight. “Why the Panic of 1907 Led to a Recession.” Accessed May 27, 2021. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/why-the-panic-of-1907-led-to-a-recession. William Edward Leuchtenberg. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal: 1932-1940. New York: Harper and Row, 1963.

William Edward Leuchtenburg. The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Winfield, Betty Houchin. FDR and the News Media. Columbia University Press Morningside ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Great Depression & The Federal Researve : An Analysis of United States Federal Government Monetary Policy from 1929 to 1934 Acknowledgements:

I would firstly like to thank Mr. Berkowitz for meeting with me and commenting on my installments throughout the course of my project. Hopefully, his help ensured that I avoided the crucial mistake of writing a book instead of a paper. I would also like to thank my girlfriend Lola, as well as my friends Ben and Luca for reading my essay for phrasing and syntax errors. They also helped ensure that my ideas were not misguided. Furthermore, thank you to the librarians Ms. Martin, Ms. Newsome, and Mr. Plonsky for their help throughout the project. They gave presentations and met with me to explain how to find potential sources of information and taught me how to use Zotero Bib. Finally, I of course have to thank my father Alessandro, mainly for instilling an interest in economics in me from a young age, but also for proofreading my essay. rticles