Pearl Harbor by US Navy Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox

At Dawn We Slept was the title of one of the most influential books about the disastrous Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on the morning of 7 Dec 1941, “a date which will live in infamy” as President Franklin Roosevelt called it in his declaration of war speech. However, I respectfully disagree with the premise of the title, as it gives the impression that the U.S. Navy was laying around the beach drinking Mai Tai’s and was totally unprepared for the outbreak of war. The reality is somewhat different.

Japanese Navy Type 99 Carrier Bomber (Val) in action during the Pearl Harbor attack (80-G-32908).

To the extent that anyone in the Navy in Hawaii was asleep the morning of 7 December, it was a sleep of exhaustion from months of intensive exercises and preparations for a war that everyone in a position of senior leadership knew was imminent, particularly the commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Husband Kimmel. The story of Pearl Harbor as it is now usually told in popular culture, that the U.S. was not expecting to be attacked, has led to a sense of complacency today; the sense that we could never be so stupid or unaware as we were back then. The reality is that the story of Pearl Harbor actually represents the razor thin line between defeat and victory against a highly capable adversary. It is a story of incredibly intense effort to get ready by some very smart people, with decisions that were made with great deliberation and purpose, some of which proved incorrect, but were not due to complacency. It is a story of an incredible effort to be ready, that was heartbreakingly close to success, but that still failed. And it should also be noted that virtually every carrier strike in WWII, U.S., Japanese and British, achieved tactical surprise, as did the multiple exercise carrier strikes conducted on Pearl Harbor in the inter-war years. (see attachment H-001-1 for more info related to U.S. Navy preparations for war.)

Readiness. The ship whose duty it was to be on alert that morning, was on alert, and performed her duty in an extraordinarily effective and efficient manner. The USS Ward (DD-139) sank a Japanese midget submarine (launched from mother submarine I-20) attempting to gain access to the harbor a little over an hour before the air raid commenced (but an hour after the Japanese strike had already launched.) In doing so, the USS Ward fired the first shot of the battle, the first U.S. shot of WWII in the Pacific, and with her second shot achieved the first kill.

Well before the attack, in response to extensive intelligence pointing toward an outbreak of hostility in the Far East and a build-up of Japanese submarines in the Marshall Islands, Admiral Kimmel had on his own initiative, and without consulting Washington, issued orders that any submarine operating in the restricted area in the approaches to the harbor, and not under positive surface escort, was to be sunk without need to refer to higher authority. Kimmel also directed that any submarine prosecution tactical communications be conducted in the clear, to ensure the widest situational awareness amongst the forces at Pearl Harbor. The duty patrol ship, the USS Ward, was manned almost entirely by enlisted reservists from the Minnesota Naval Reserve, who had been activated on 21 Jan 41 and deployed on 23 Jan 41, to bring the Ward, inactive since WWI, into operational status. The ship’s CO, LT William Outerbridge (USNA ’27), had been in command less than two days, but nevertheless acted immediately and decisively to attack the submarine as soon as it was spotted by the supply ship USS Antares (AG-10) attempting to trail her into the harbor at 0645, coordinating with a PBY Catalina flying boat as he did. Closing the sub at 20 knots, Ward opened fire with 4″ gun #1 (bow) at 100yds and just missed over the sub’s conning tower. Gun #3 (amidships, starboard) fired at 50yds and scored a direct hit at the base of the conning tower, which proved fatal, and was a feat of gunnery greeted with some degree of skepticism until the sub was found in 2002. As Ward passed between the submarine and the Antares, she rolled four depth charges over the stern, which detonated 100′ under the sub, which was observed to roll over and sink.

The PBY dropped depth charges on the datum as well. At 0653, Outerbridge passed the first of several clear voice and coded messages, with his second message in the clear stating what he hoped was unambiguous, “we have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges upon submarine operating in the defensive sea area.” While previous false reports had been numerous, firing on a target was something new. The watch officer ashore reacted with alacrity, and the duty destroyer USS Monaghan was quickly notified to get underway and assist. However, a linear, sequential notification process was slowed by “busy signals” and multiple requests to have the Ward re-confirm the report before passing it up the chain. Nevertheless Kimmel was notified at 0735, cancelled his regular golf game with General Short (unlike in the movie Pearl Harbor), and was on his way into the headquarters in reaction to the report when the air attack commenced at 0755. (see attachment H-001-2 for more on the USS Ward)

Valor. Although Pearl Harbor was a devastating tactical defeat resulting in 2,403 U.S. military and 68 U.S. civilian deaths, the vast majority of U.S. Sailors responded immediately and in many cases with extraordinary acts of bravery, many of which were unrecorded due to the deaths of so many witnesses.

Even so, Navy personnel were awarded 15 Medals of Honor, 51 Navy Crosses, and (somewhat anomalously) four Navy-Marine Corps Medals; the most medals for bravery under fire for a one-day action is U.S. naval history. Medal of Honor recipients included; Rear Admiral Isaac Kidd and Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh, killed at their post on the bridge of USS Arizona (BB-39) when she exploded; Captain Mervyn Bennion, skipper of the battleship USS West Virginia (BB-48), who attempted to continue to fight his ship even after being mortally wounded by shrapnel; Commander Cassin Young, skipper of the repair ship USS Vestal (AR-4) moored alongside the Arizona, blown clear off the bridge of his ship into the water, nevertheless climbed back on board and got his sinking ship underway and beached it so it would not be an obstruction.

Other Medals of Honor included Chief Boatswain Edwin Hill of the USS Nevada (BB-36), the only battleship to get underway during the attack, jumped into the water, swam to the mooring pier, cast off the lines, swam back to the Nevada and got on board, and was leading actions on the forecastle in preparation to beach the ship, which had attracted numerous Japanese dive bombers, when he was killed by strafing and bomb explosions. Among the Navy Crosses was Ensign Joe Taussig, Jr. (son of Commander, and later VADM, Joe Taussig of WWI “we are ready now” fame) who continued to direct the Nevada’s anti-air defenses even with a leg amputating wound. Another Navy Cross was awarded to Messman Third Class Doris Miller, for aiding the dying Captain Bennion on West Virginia under fire, before manning a .50 cal machine gun, on which he had not been trained, and assisting in the downing of more than one Japanese aircraft. Miller was the first African American Sailor to receive the Navy Cross, and of note, Miller’s actual battle station, one of the 5″ gun mounts, was destroyed by one of the first torpedoes to hit West Virginia, which is why he ended up on the bridge. (see attachment H-001-3 for more of valor at Pearl Harbor)

“Neutrality” Patrol

For those in the Atlantic, although 7 December is marked as the entry of the U.S. into WWII, the fact is that the U.S. Navy was already in an undeclared shooting war with Nazi Germany at sea well before that. President Roosevelt and other senior U.S. and political leadership were convinced that England could not be allowed to fall. U.S. Navy leaders were particularly concerned about the possibility that the Royal Navy could fall into Nazi hands (as did most of the French Navy, before the British unilaterally sank most of it) which would dramatically increase the naval threat to the United States.

As a result the U.S. pressed the envelope on “neutrality” and in many cases technically exceeded it, and multiple such “violations” were cited in Germany’s declaration of war against the U.S. after Pearl Harbor. In agreement with the British, U.S. Navy assets were escorting trans-Atlantic convoys across “our side” of the Atlantic as far as Iceland before handing them off to British escorts, frustrating German U-boats, who were under orders not to attack U.S. warships, although identification could be challenging (especially after we “loaned” the British 50 WWI-vintage four-piper destroyers.) On 10 April 1941, USS Niblack (DD-424) dropped depth charges on a German U-boat without result, but arguably the first U.S. “shot” of WWII.

On 4 Sep 41, USS Greer (DD145) was prosecuting U-652 and providing information to a British patrol bomber, which dropped depth charges on the submarine. U-652 retaliated by firing a torpedo at Greer, which missed, and Greer responded with an unsuccessful depth charge attack. At the time, U.S. Navy ROE allowed passing tactical data to the British, but otherwise limited U.S. forces to self-defense. The Greer incident resulted in new ROE approved by President Roosevelt, which became known as the “shoot-on-sight” order allowing U.S. ships to attack any U-boat detected.

On 17 October, USS Kearney (DD-432) responded to a wolf-pack attack that had overpowered the Canadian escorts of a convoy and conducted several depth charge attacks on German U-boats before being hit and damaged by a torpedo fired by U-568, killing 11 U.S. Sailors and wounding 22 more. As the conflict continued to escalate, during daylight on 31 October, USS Reuben James (DD-245) positioned herself between an ammunition ship and a German wolf-pack, and was hit by a torpedo from U-552 intended for a merchant ship (so said the Germans). The torpedo detonated the forward magazine, blowing the bow off the ship, and causing the Reuben James to sink within 5 min. Only 44 enlisted Sailors and no officers survived of her crew of 136 enlisted and seven officers. At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. political and military leadership viewed the Atlantic Theater as paramount, and numerous naval assets, including aircraft carriers and battleships were diverted from the Pacific Fleet. In particular, the priority basing of long-range patrol aircraft to the Atlantic was a critical factor in the acute shortage of such aircraft (and trained crews and parts) at Pearl Harbor which contributed significantly to the Japanese surprise.

This photo (NH 97446) was taken of the USS Ward (DD-139) shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack. It shows the number three 4″/50 mount and its crew, consisting of Naval Reservists from Minnesota. This gun survives today and is located in a park near the grounds of the Minnesota state capitol. The original U.S. Navy official caption, as well as the plaque on the gun today, erroneously states that this gun fired the first shot during the Pearl Harbor raid. Gun #1 fired the first shot, which missed. Gun #3 fired the second shot, which hit and sank the Japanese midget submarine. USS Ward only fired two rounds during the engagement.

Navy Valor at Pearl Harbor

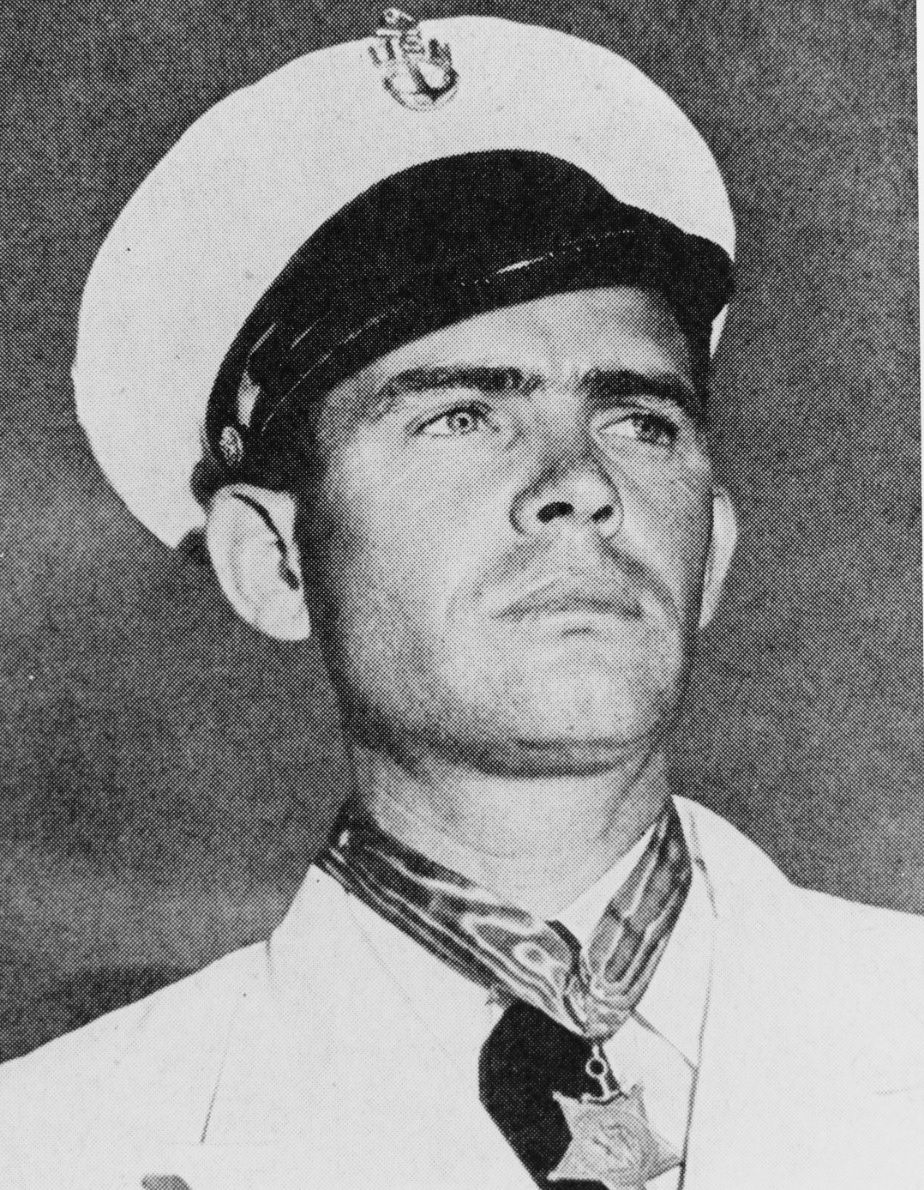

Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John W. Finn, USN (NH 95448).

Medals of Honor Awarded to Navy Personnel

Captain Mervyn Bennion – posthumous. USS West Virginia, commanding officer. Despite being mortally wounded, showed no concern but to continue fighting and save his ship.

Chief John Finn. Naval Station Kaneohe Bay. Despite numerous painful wounds continued to man a .50 cal machine gun in the open continuously firing at Japanese aircraft despite intense strafing.

Ensign Francis Flaherty – posthumous. USS Oklahoma. Sacrificed his life to ensure remainder of his turret crew could escape.

Lieutenant Commander Samuel Fuqua. USS Arizona. As the senior surviving officer after the explosion that destroyed the Arizona, he remained on board directing damage control, firefighting and rescue efforts.

Chief Boatswain Edwin Hill – posthumous. USS Nevada. Swam back to the ship after casting off the lines. Subsequently, after directing his men to take shelter, he was killed by bomb explosions and strafing in an exposed position on the forecastle attempting to let go the anchors as the Nevada was beached.

Ensign Herbert Jones – posthumous. USS California. Despite fatal wounds, organized and led a party supplying ammunition to the anti-aircraft batteries.

Rear Admiral Isaac Kidd – posthumous. USS Arizona. As Commander of Battleship Division One, he discharged his duties as Senior Officer Present Afloat (SOPA) until the Arizona blew up.

Gunner Jackson Pharris. USS California. Despite severe wounds, on his own initiative, set up a hand-supply for the anti-aircraft guns, and repeatedly risked his life to save other shipmates.

Radio Electrician (Warrant Officer) Thomas Reeves – posthumous. USS California. Passed ammunition by hand in a burning passageway to anti-aircraft guns after the mechanized hoists were put out-of-action, until overcome by smoke and fire.

Machinist Donald Ross. USS Nevada. Single-handedly kept the forward dynamo room operating, after ordering his men to leave due to smoke, steam and heat, despite being blinded.

Machinist Mate First Class Robert Scott – posthumous. USS California. Remained at his post at an air compressor as it flooded to ensure the anti-aircraft guns had air as long as possible.

Chief Watertender Peter Tomich – posthumous. USS Utah. Remained at his post in the engineering plant of USS Utah as she capsized, securing boilers and ensuring the escape of all fireroom personnel.

Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh – posthumous. USS Arizona. As Commanding Officer, valiantly fought his ship until killed in the magazine explosion.

Seaman First Class James Ward – posthumous. USS Oklahoma. Sacrificed his life so others in his turret crew could escape.

Commander Cassin Young. USS Vestal. As commanding officer of the Vestal, was blown overboard by the force of the Arizona blast, but returned to his ship and despite two more bomb hits, got his sinking vessel underway and moved to where it would not be an obstruction.

Pearl Harbor by US Navy Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox

Samuel J. Cox (SES)

Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Director of Naval History

Curator for the Navy

Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

Originally published on Navy Valor at Pearl Harbor